The Banal in Our National Identity

Propaganda that we conformed to

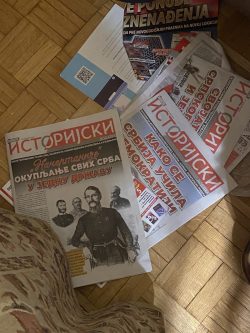

Photo credits: ANĐELA BUCALOVIĆ

I’m writing this article partly because I want to continue to explore my own relation to national identity and how it affects me. For that, I need to go through the looking glass. To see myself I need to understand the wider structure – part of the society I grew up in. I must learn more about the circumstances and surroundings that influenced my feelings and the sense of belonging to my nation. I adopted many statements and misinformation as facts just because it was widely socially accepted. Now, although I know better, the claims can still pop up sometimes in a feeling, as a residue attitude that I can’t quite define.

Banal Nationalism: Unmasking Everyday Nationhood

National identity is built as a collective and generational identity that you as an individual have no immediate influence over. It can be stressful to adapt to it when it doesn’t fully align with your personal values and beliefs but even more terrifying to be outside of it – if it creates a sense of safety in belonging, and stability for your mental health. To adjust, it’s important to comprehend the subtle systems enforcing national identity.

Let’s start with the concept of banal nationalism.

Exploring the concept of banal nationalism, coined by Michael Billig, was a turning point in my understanding of national identity. It reveals how everyday symbols – flags, slogans, names of public places, even graffiti – subtly embed notions of nationhood in our minds. As I observed these symbols around me in Belgrade, I began to see how they form a backdrop to our daily lives, influencing our perceptions without our conscious efforts. This awareness made me question the deeper narrative being chained through our media, where these symbols often find more potent forms, displaying fascism and evoking hatred.

Photo credits: TAMARA PAVLOVIĆ

Enters: Media

The role of the media in the formation of collective identities is commonly known. It is a powerful construction and dissemination tool for building and reinforcing national identity, and in a utopian world, it would be a great unbiased source of information. The world we live in, and I live in Serbia, doesn’t stand a chance against the bias, lies, and distortion of facts, thrown at it daily by government-controlled (“supported”) media. The Constitution of Serbia prohibits censorship, and freedom of expression and information are protected both by national and international law. So why don’t we trust the media here?

With the social media rise, especially since TikTok was introduced, media houses are gasping for air, and the government money infusion is their mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

When the State announced in 2014 its withdrawal from media ownership in Serbia, briefly, it sparked a collective sense of optimism. I shared this hope, envisioning a new era of transparent and impartial journalism. But this hope was short-lived. An article by N1 in 2019 highlighted the paradox of the official withdrawal of the state from media ownership, yet the government’s influence has never been more pronounced. The research conducted by BIRN and RSF flashed the light, revealing heightened government interference between 2017 and 2019. This dissonance between expectation and reality struck a chord with me, underscoring the complexity of the media landscape I had grown up with and its influence on my understanding of our national narrative. Today, reports on democracy around the world such as Freedom House Reports, ring the alarms – the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) has steadily eroded political rights and civil liberties, putting pressure on independent media. Serbia, we have a problem.

Photo credits: ANĐELA BUCALOVIĆ

Media Influence During the Yugoslav Wars

Photo credits: ANĐELA BUCALOVIĆ

Scholars argue that effective hate propaganda can transform ordinary people into perpetrators of violence by making violence seem necessary and justifiable.

I came across a paper, Helena Ivanov’s PhD thesis “Inside Propaganda Serbian Media in the Yugoslav Wars 1991-1995”. It provides a detailed analysis of the role and techniques of propaganda during the Yugoslav Wars, focusing specifically on the media outputs of Serbia. Finding this article almost felt like an exciting discovery that would change my life. I craved to read something that would help me understand the origins of our current reality. The strength of the article is in the thorough examination of how propaganda shapes perceptions and justifies violence, offering valuable insights into the complex interplay between media and conflict. Still, I felt quite uncomfortable and dissatisfied by the end of reading it. The article is incredibly valuable literature, but the Serbian in me was still triggered. I was feeling sad or rather frustrated. It seemed like justice wasn’t done by examining only one of the perpetrators. I want to read more about the same influence in the rest of the involved countries…

While it’s valid to feel this way, I realize that the scope of the matter is too broad and this is still an impressive analysis of what has been done. Not by every Serbian, not by me, but by the government and the media propaganda in Serbia. It is important to take accountability and put the responsibility where it should be!

Conclusion

I never considered myself much of a patriot. I try to see people for what they show me – by their actions, not the labels they might put on themselves or what they have put on by society. I don’t have all the answers but the fact that I felt disturbed, that I am sure many of you feel once your national identity is called out in any way, testifies best to how deeply the roots dig, and create some of the links to our national identity.

I don’t think it’s possible to tell where the beginning is in the loop of time that we are living in. I also believe that there is no real truth, only the perception of the observer. So I wouldn’t try to persuade you that there is a particular person or event to blame for the state that we live in. However, I do want you to take accountability for being an accomplice in maintaining the status quo, and not using your attention to become a more conscious consumer of the world around you. Wherever you might live, this is not a problem exclusive to Serbia.

Explore further what ties into the media propaganda and our conformation to it.

Photo credits: ANĐELA BUCALOVIĆ